How much does a big mac cost in yuan in china mac#

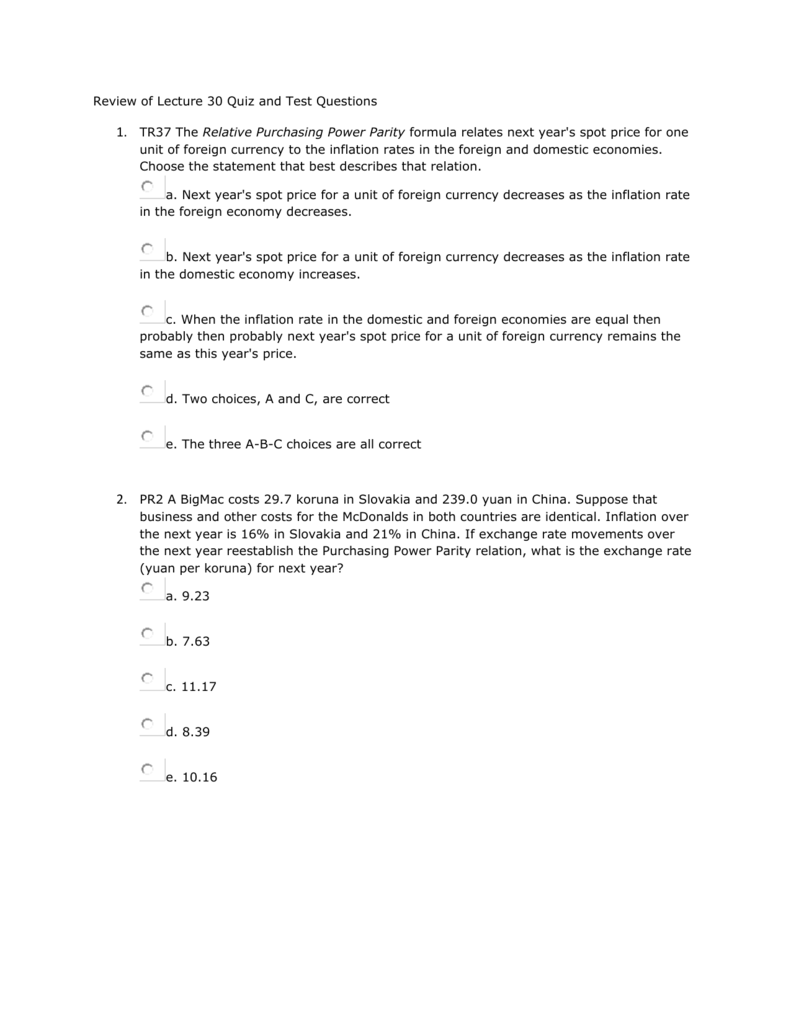

On the other side of the spectrum, a Big Mac in Ukraine only costs $1.67. On the expensive side of things, a Big Mac will run you $6.82 in Switzerland. In the middle of the spectrum, we have the home of the Big Mac, the USA, where one of these iconic burgers costs USD $5.30. The latest data from the Big Mac Index provides ample proof of that. Basically, the theory behind PPP is that, over time, the price of a given “basket” of similar goods in any two countries will tend to equalize - in this case that "basket" is a burger- and the more equalized the basket price is, the more parity between countries. The Big Mac Index was originally cooked up (yes, pun intended) as a generally good-natured way of comparing the Purchasing-Power Parity (PPP) of different countries. At least that was the idea The Economist magazine had when they introduced the Big Mac Index in 1986 to convey country-by-country consumer purchasing power. The American may have more to spend, but the Chinese guy can stretch his yuan further.Yes, you read that right: The mighty Big Mac can tell us a lot about a country's economy. However, the American lives in the United States and has to purchase products and services at US prices while the Chinese man lives in China and pays Chinese prices. The American man would have so much more money than his Chinese counterpart. As I understand it, a simple way of thinking about this is imagining a Chinese man and an American man meeting and turning out their pockets. Using the PPP figures, economies like China and India are much larger than with market exchange rates China is the 2nd largest world economy by PPP reckoning.

The two ways of determining the value of currency (and, eventually, the size of a country’s economy) have different results. Meatier and more sophisticated estimates of PPP, such as those used by the IMF, suggest that the required adjustment is even bigger. If China’s GDP is converted into dollars using the Big Mac PPP, it is almost two-and-a-half-times bigger than if converted at the market exchange rate.

One big implication of lower prices is that converting a poor country’s GDP into dollars at market exchange rates will significantly understate the true size of its economy and its living standards. A hair-cut is, for instance, much cheaper in Beijing than in New York. But the prices of non-tradable products, such as housing and labour-intensive services, are generally much lower. The prices of traded goods will tend to be similar to those in developed economies. It is quite natural for average prices to be lower in poorer countries and therefore for their currencies to appear cheap. That a Big Mac is cheap in China does not in fact prove that the yuan is being held massively below its fair value, as many American politicians claim. Yet these very failings make the Big Mac index useful, since looked at another way it can help to measure countries’ differing costs of living. Burgers are not traded across borders as the PPP theory demands prices are distorted by differences in the cost of non-tradable goods and services, such as rents. The Big Mac index was never intended as a precise forecasting tool.

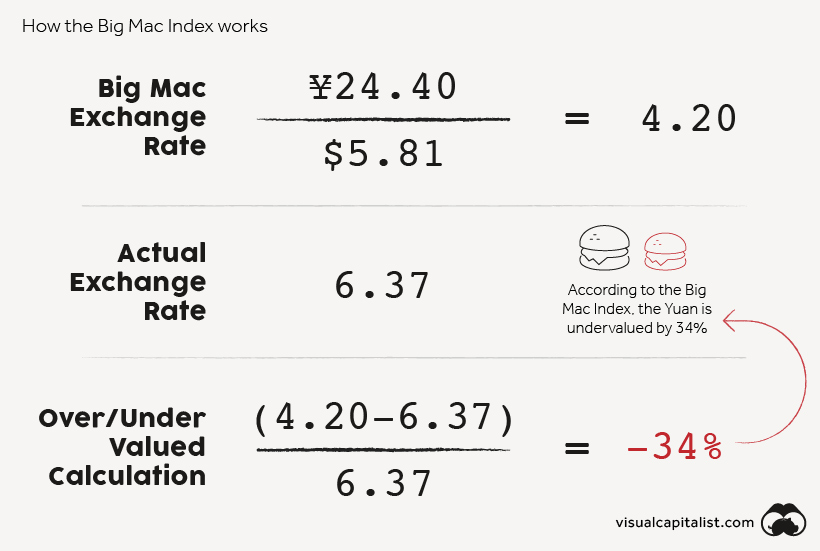

By comparing the prices of burgers in different countries, you can come up with an exchange rate and compare that to conventional market exchange rates and determine if a country’s currency is over- or under-valued, Mac-wise: The Economist reports on using the McDonald’s Big Mac as an economic indicator.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)